Jay Rosenblatt Focus

← All ProgrammingHis works have won over 100 awards and been screened around the world. A special retrospective was dedicated to him at the Film Forum in New York, which toured theaters across the United States. He also had a week-long feature film program at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

Nine of his films were selected for the Sundance Film Festival, another nine for IDFA (Amsterdam International Documentary Film Festival), and several were broadcast on HBO, PBS, and the Sundance Channel. His work has been featured in publications such as the New York Times (Sunday Arts & Leisure section), Los Angeles Times, and Filmmaker Magazine.

Rosenblatt is a fellow of the Guggenheim, USA Artists, and Rockefeller foundations. He has been a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences since 2002 and served on the Documentary Branch Executive Committee for twelve years.

A native of New York, he has lived in San Francisco for many years. Between 1989 and 2010, he taught film and video production at various schools in the Bay Area, including Stanford University, San Francisco State University, and the San Francisco Art Institute. For 15 years, he was Program Director of the Jewish Film Institute (responsible for the San Francisco Jewish Film Festival). He has a Master's degree in Counseling Psychology and, in a previous life, worked as a therapist.

Jay Rosenblatt

Jay Rosenblatt’s Archival Retrospections

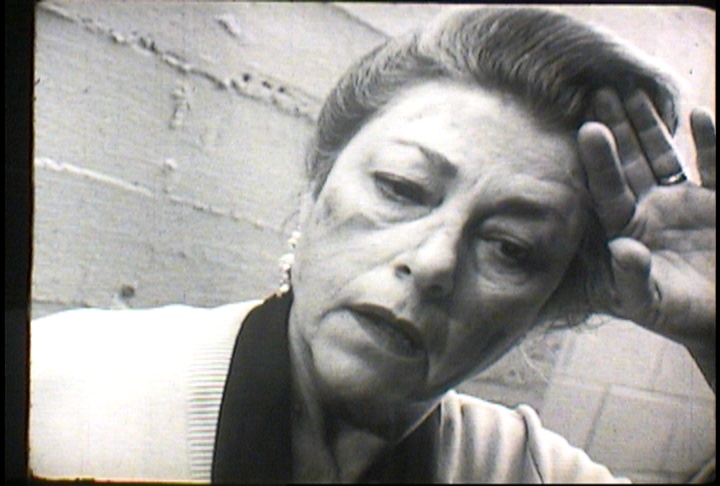

Many of Jay Rosenblatt’s audiovisual collages serve as a coming to terms with the filmmaker’s own, often painful life experiences. On one hand, much of his oeuvre concerns his specific traumas of growing up in a Jewish family in New York City in the 1960s, of being threatened by bullies and sometimes becoming a bully, of losing his brother at a young age.

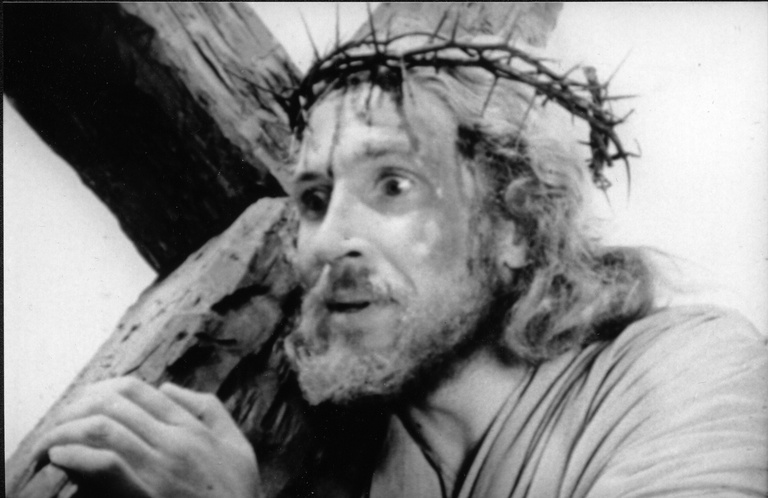

The Smell of Burning Ants (1994), for instance, focuses on the experience of being male in the violent and threatening milieu in which Rosenblatt was socialized, surrounded by bigger boys looking for any sign of weakness in their peers. King of the Jews (2000), meanwhile, emphasizes the bewildering experience of growing up Jewish-American in the decades following the Holocaust, always aware of the never-ending precarity of Jewish life. On the other hand, Rosenblatt’s films articulate the much broader experience of being a gentle, perceptive soul thrust into a world too frequently populated by sadists – from schoolyard tyrants to mass murderers – in which nearly everything is beyond the individual’s control. To unearth the links between his unique personal experience and those more universal human struggles, Rosenblatt chose a very particular path: searching for glimpses of his likeness – his existential kin – in the cinematic archive.

Jay Rosenblatt

Like the human psyche, the archive is haunted. As a vast but also devastatingly incomplete repository containing the written, visual, and audial traces of the past, it is the ideal place for Rosenblatt to seek echoes of his own ghosts, finding them especially in discarded educational films, industrial films, and newsreels. By locating, selecting, arranging, and juxtaposing found sounds and images with text and voiceover, Rosenblatt tells his own life stories – of bullying to avoid being bullied, of trying to understand antisemitism and the Holocaust and the death of his brother – through others’ faces and voices, which he then entwines with images of his own family. Indeed, the underlying themes of his films are those that nearly every human being shares: of having a family, with all the love and rage and guilt that necessarily entails; of the pain of growing up; of experiences of power and of powerlessness. In his complex repurposing, Rosenblatt editorially interweaves the collective unconscious of the cinematic archive with his own psyche. Indeed, when he mixes educational footage with 8mm movies shot by his own parents, the viewer of his work may sometimes find it difficult to distinguish one from the other. This is not, however, a reduction of self to other or vice versa; rather, it is an act of archival retrospection – a looking back, into the remains of the cinematic era, now at its close – in search of kinship with the dead and with the audience

Jay Rosenblatt

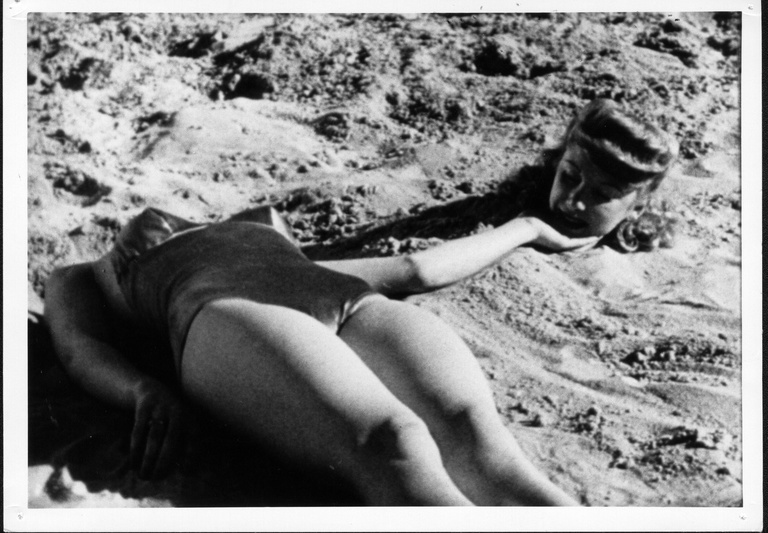

In some of his more recent work, Rosenblatt has shifted away from mining the extant public archive to producing his own private archive, particularly of his daughter Ella’s birth and childhood, and then applying his strategies of archival retrospection to his experience of parenthood. To some extent, watching these films feels like watching a stranger’s most personal home movies; and even in the age of frantic digital exhibitionism we currently inhabit, this act can feel voyeuristic and intrusive. Heartbeat (2025), in particular, which retrieves from Rosenblatt’s domestic archive footage that he and his wife and collaborator Stephanie Rapp produced while they were trying to have a baby, can read as too intimate, an overexposure.

Yet, the thoughtful, retrospective lens of the film is what distinguishes it from the domestic exhibitionism now rampant online. Because the footage was recorded nearly a quarter century ago, the time elapsed transforms this intimate footage into a record of feelings felt long ago, long enough that they can mean something different now. These anxious images can be handled precisely because of the temporal distance afforded by an archival, indexical medium and may be subsequently transformed into a narrative of an experience others may – at least partially – recognize. A related film, How Do You Measure a Year? (2022), is at once a series of home movies, a longitudinal documentary, and a sort of structuralist experiment, in which Rosenblatt asked his daughter the same set of questions on her birthday every year between the time she was two and eighteen, recording her answers.From one perspective, this record of someone else’s beautiful child growing up is really none of our business; from another, however, it can be read as a careful and sustained imaging of time’s passage, of growth and transformation as inscribed in the face and body of one’s most beloved. By creating an archive of his own family life, Rosenblatt becomes a retrospective authoethnographer, treating the traumas of his own past while also reminding us – despite it all – of the joys of still being alive and never quite knowing what will come next.

- Jaimie Baron (August 2025)

Focus Jay Rosenblatt

Focus#1 Jay Rosenblatt

Batalha Centro de Cinema

Focus#2 Jay Rosenblatt

Batalha Centro de Cinema

Focus Jay Rosenblatt

Batalha Centro de Cinema

Focus#3 Jay Rosenblatt

Batalha Centro de Cinema

Focus#4 Jay Rosenblatt

Batalha Centro de Cinema

Focus#5 Jay Rosenblatt

Batalha Centro de Cinema